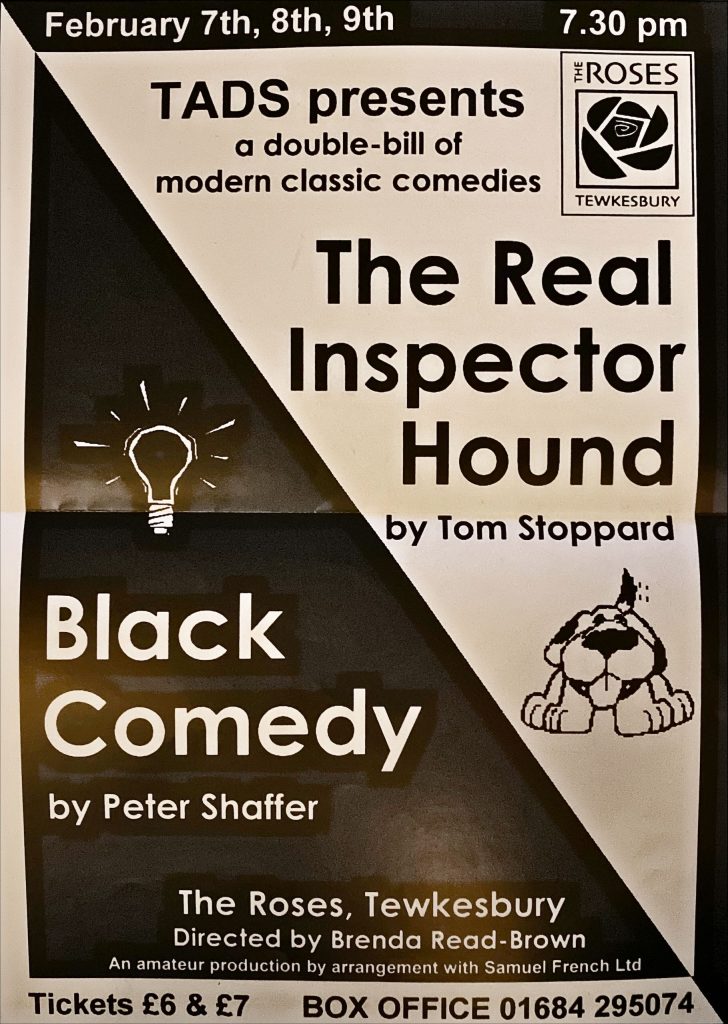

These productions were entered into the Gloucestershire Drama Association’s One-Act Play Festival.

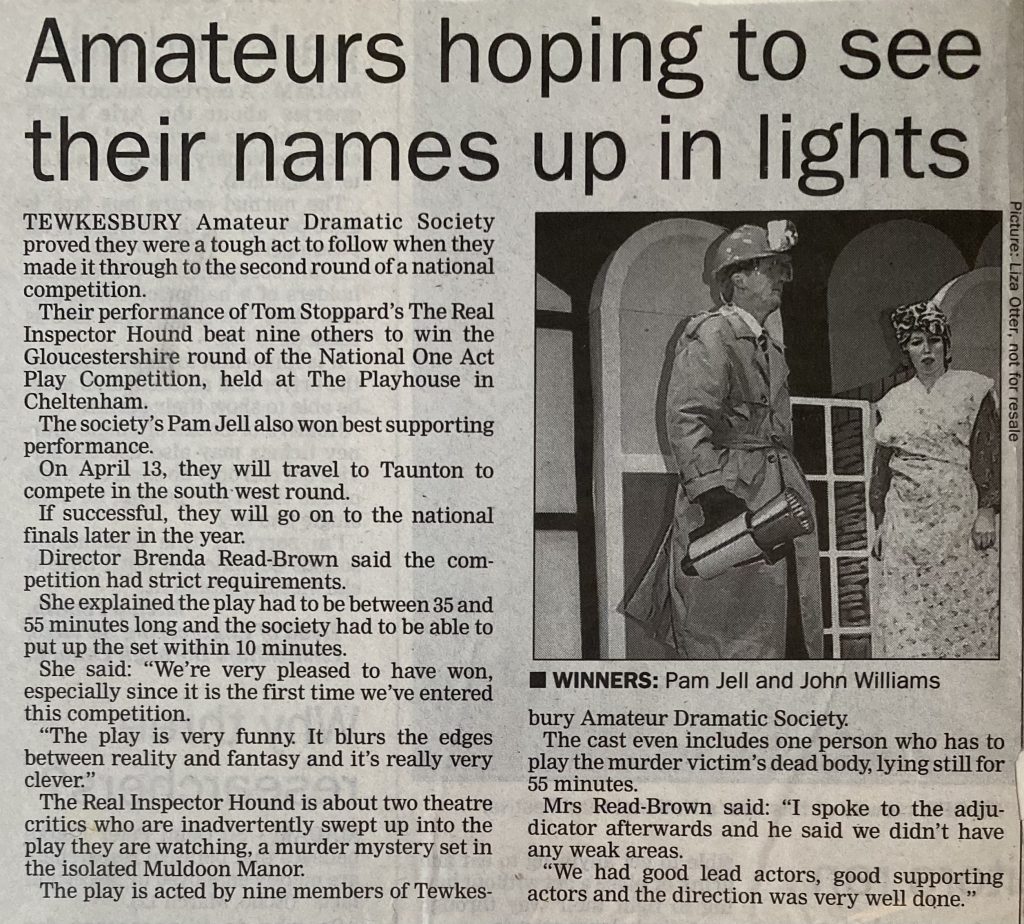

The Real Inspector Hound won the Gloucestershire round and went on to have a magnificent run in the All England Theatre Festival competition for one-act plays with performances in March, April and May 2003; just failing to qualify for the National Finals. Pam Jell also won the award for Best Supporting Actress.

The GDA Adjudicator’s Full Report:

Non-competitive adjudication

“Although there had been occasional low key pairings of these two plays, the first time they appeared together in the West End was for a six month run in 1998, thirty years after the newest of them was written. Both were written following huge critically acclaimed full-length plays, Stoppard’s ‘Rosencrantz and Guildenstein are dead’ (which shares with ‘Hound’ a playful approach to theatre) and Shaffer’s ‘Royal Hunt of the Sun’, both were descended upon by amateur groups early on and both share a lateral, slightly surreal view of reality, with ‘Hound’s stage/auditorium trick set against ‘Comedy’s light dark switch. The style, length and opportunities for actors (5 males and 3 females) together make them an ideal combination for inclusion in any ensemble’s programme of performances. My own connection with the plays started with student performances of the Stoppard play in the late sixties and an absolutely superb 1971 introduction to Shafter’s at an amateur performance at The South London Theatre Centre (my very pregnant wife almost gave birth in the stalls, we laughed that much). There followed countless performances of varying quality over the next three decades until two performances of the paired plays seen last year, the professional version that visited Malvern and an amateur version by The Little Theatre at Cheltenham’s Playhouse Theatre. I think on these plays as being akin a furniture maker’s scaled down trial pieces, clever and detailed, demonstrating a master’s expertise but, while there are layers of understanding within them, neither carries any real significance beyond that of an entertainment. Stoppard quoting a friend some years later said that ‘The Real Inspector Hound’ was ‘as useful as an ivory Mickey Mouse.’ – but both his play and Shaffer’s are much more fun than that aren’t they?

Your programme had a complementary feel about it, with the one play reading from the front and the other from the back – but which was the front? Which play was to start the evening? On the previous occasions when I had seen the plays together ‘Hound’ had begun the evening and I certainly favour that order of presentation, with that play warming the audience to be followed by houselights dimming, the curtain opening to – what? Blackness! – Of course this is BLACK Comedy’! This recognition encourages an audience response from those new to the play, with support from those who remember their first time, and there is still to come the transformation to the stage that serves to enhance the power cut moment. I felt that this lack of anticipation was an opportunity lost. I still remember this delicious moment from my own first acquaintance with the play.

There are clearly health and safety considerations for the blackout section but I felt that the brightly painted trim to the flats was too visible and compromised the darkness a little. When the set was revealed there was certainly a sixties feel to it, with the bright end of the paint colour chart well in evidence – pinks, yellow, purple and orange – with dome shapes and a fairly swinging ambience. The trapdoor was efficiently located and the studio well placed fronted by a curtain under the well-considered bedroom on a raised section; this certainly enhanced Miss Furnival’s drunken entrance. The furniture was appropriate and manageable given the stage business that it must serve, although I felt there should be more of Brindsley’s artistic aspirations in evidence, as some of the art works on view were rather awkwardly mounted on the walls and extra canvasses could have been propped against walls in corners or in the bedroom for example. There was a consistency to the look of the stage however, with the stage dressing complementing the stage environment. The room did seem to be too large though and, while the action was directed to inhabit the whole stage, I felt that the claustrophobia of the situation could have been enhanced by reducing the acting width of the stage, and this would have increased the intensity and pace of the action, reducing the amount of light on stage in blackout and providing a location more suggestive of Brindsley’s social standing, although this would have some clear repercussions upon the blocking of the scenes. A reduced stage for the one play would have opened opportunities for a contrast with the other play, the location for which did require the full width of the stage, due both to the class of the characters and the murder/mystery stage situation. Notwithstanding the added flats with beams and the grey-walled flat at the French windows, the colouring of the set stayed the same for this play, although all other aspects of the play pointed to a date much earlier in the century. There was a compromise on Stoppard’s suggestion of an audience mirrored on stage but the use of the erstwhile bedroom for the critics was a neat solution although a low wall or curtain would have given more sense of an auditorium box and exposed them less. I also wondered whether the stage left door in ‘Black Comedy’ on this occasion could have opened on downstage hinges to obscure the unlit hail, which, to stay consistent of course, would have been brightly lit rather than in shade. In spite of the slight misgivings mentioned above, the sets did occupy the stage space effectively for both plays and they were efficient solutions to the problems set by the plays with the transformation from one play to the other impressively undertaken by the stage hands.

Sound and lighting were well controlled, appropriate and complemented the action. I particularly liked Hound’s horn and the timing of the reduction of light was impressive although I would have favoured less light still when matches were struck or the torch was turned on. It must be a sign of time passing that the bell of the telephone was obviously recorded in this age of warbling mobiles. It was a shame that the marching music had but a matter of seconds to become established before the cut, as the wind down of sound would have been more effective at part of a sequence rather than part of the same moment. There was also rather too quick a telephone cue after Was that you? I thought it was Higgs.’ not allowing enough time for the irony of this line to register.

Again the selection of these minor examples serves to demonstrate very good levels of overall success.

Costume was serviceable rather than a creative highpoint of the plays. The first play has splendid potential as an opportunity to delve into swinging sixties gear, with debutante Carol contrasted to trendy Clea, Harold taking advantage of the bolder colours available and acceptable then and the Colonel looking distinctly conservative against the colourful fashion of the others. Instead there was a disappointing greyness to the assemblage that suggested a timelessness not born out by the play’s references to the Beatles for example. Miss Furnival’s sensible two piece and Bam Berger’s caramel coloured coat were the most effective costumes in some ways, the latter seem much younger than the preceding description suggested. The second play had more sense of costume although there was a lack of overall design with Cynthia’s Nlapper isolated against the classless other costumes, and Felicity’s cork sandals were really at odds with character and situation. Hound’s boots provided a textual necessity but their construction was all too apparent and Moon’s anorak seemed rather

ill suited to character and situation. However for the most part, as much as the costumes did not impress, they certainly did not hinder the actors in their performances.

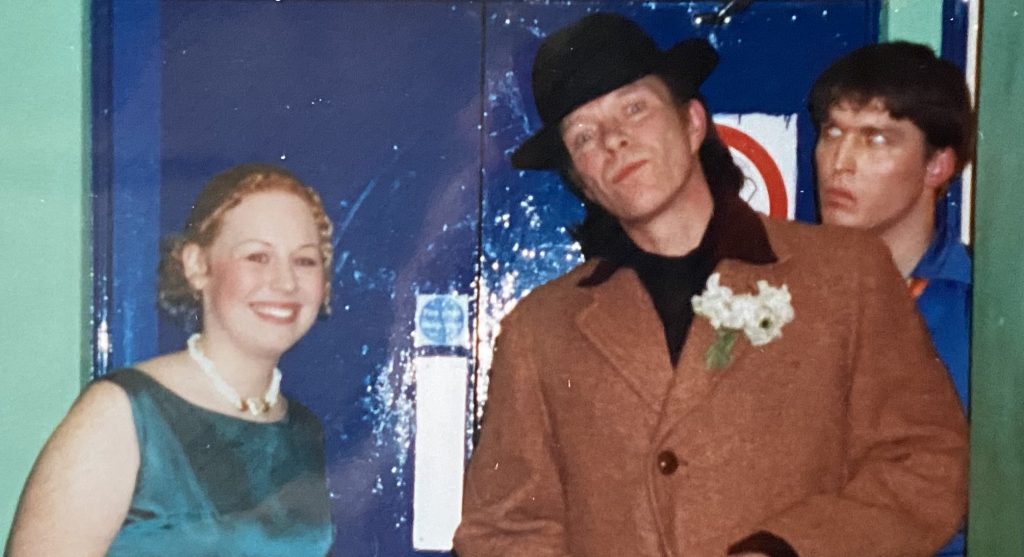

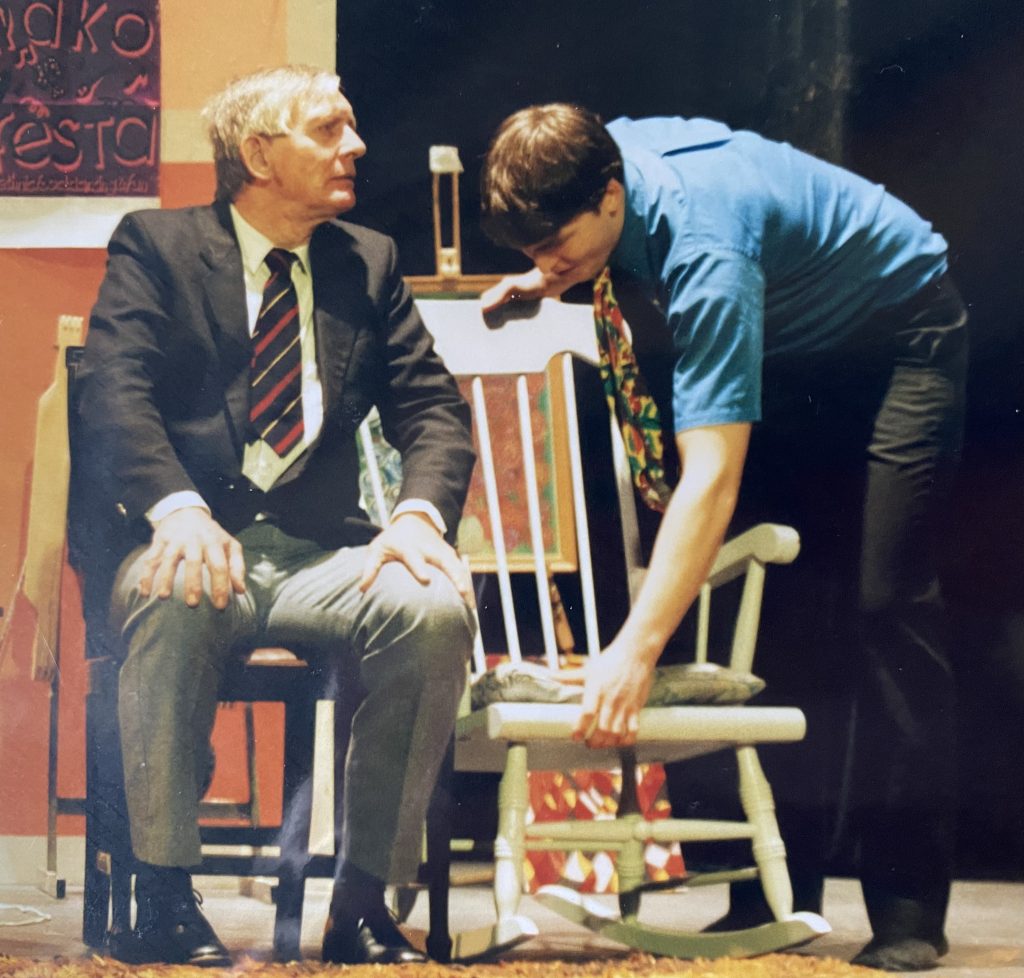

That these plays are audience pleasers was clearly demonstrated on Saturday night and there were many occasions when you elicited hearty responses from the impressively sized audience, the third of such I understand, but they are also splendid plays to direct and within which to act, giving as they do such wonderful opportunities for creative rehearsal work, and one can only guess at the joy of invention for the authors. Your actors worked very hard and none did less than a very creditable job. The sheer superficiality of the characters is a gift for the actors as the stereotypes required are embraced and celebrated. The range in ‘Black Comedy’ extends from Carol’s quacking dab to Harold’s priggish queen, from Miss Furnival’s burgeoning alcoholic to the Colonel’s ‘P.E.”! All are beautifully supportive of the plot and all have little or no currency outside this tightly written stage environment. The West End production had the same eight actors in both plays but had the actors play contrasting characters and, given the cast, I think this a good idea as the display of acting range seems consistent with the virtuoso style of the plays. You avoided the duplication of character by extending the cast beyond the eight, for an actress playing both Mrs Drudge and Miss Furnival would certainly impress less than one who played contrasting roles. William Tombs and Sarah Dolphin began the evening’s entertainment on the darkened stage delivering Shaffer’ clever opening expository dialogue. Sarah’s carefully enunciated tone of voice struck a good balance between clarity for the audience sake and being really irritating as the character of Carol. When the lights snapped on she gave a fair impression of the disorientation the character might experience and her mid distance eye focus was well sustained. I have seen Carol played as a wronged woman and felt that this skewed the audience sympathies, for Carol is a monster, manipulative and twee, and Sarah gave us some of this in her characterisation with her sour facial expression, childish language (Daddypegs’ indeed!) and haughty posture, although I would like to have seen more range in her movement across the stage which became rather settled into a jack-knife body shape with arms outstretched. William had the most stage business difficulties to overcome and he made a fair jot~ at doing so, the incidents with the rocking chair and the foot in bag handle stand out as excellent examples of a man trapped in a situation where inanimate objects lay traps. Vocally he was not always clear, some lines were delivered with insufficient intonation to convey his plight and he did not quite communicate the character of artist; resourceful when cornered yet romantically connecting with not only Carol but the atavistic Clea and also the vengeful Harold. He did keep the pace fairly crisp and the exchange of furniture was well handled. He also covered for the unbroken Buddha most effectively. His Simon in ‘Hound’ was suitably shifty and he worked well with the rest of the cast. He clearly has ability and with a little more experience he will undoubtedly impress in the future.

John Elliott’s camp Harold Gorringe delivered his lines with a lightness of tone and a limpness of wrist that left the audience little doubt as to his aesthetic (1) tastes. His fondness for Brindsley was well conveyed although I would like to have seen more of the predatory side of him and also the potential danger he represents for his untrustworthy neighbour. He delivered the pathetic silly, stupid trusting me’ section to very good effect. Clea’s first appearance at the door is at just the right time to further enmesh Brindsley in his self inflicted trap and Ann Vincent contrasted effectively with the rather silly Carol, reacting silently yet venomously as she hears Brindsley’s lies. She could have made a little more of Mrs Punnet as the part gives her rare licence to overact to maximise both the stage embarrassment and also the audience enjoyment. She had some nice moments in the darkness between Brindsley and Harold and with the bottle of liquid, a good supportive performance.

Arguably the most rewarding part in the first play is that of Miss Furnival, a moral bastion who under cover of darkness descends towards depravity, silently demolishing the bottle of gin to emerge from the studio dishevelled and missing a shoe. Janet Lines did not disappoint in her portrayal with upper class fragility and reticence giving way to drunken swagger in a manner reminiscent of Beryl Reid in Entertaining Mr Sloan’. The timing and impact of her final entrance was most impressive. Richard Hughes gave another well-considered cameo performance in the short role of Bamberger disappearing through the trapdoor with fitting aplomb.

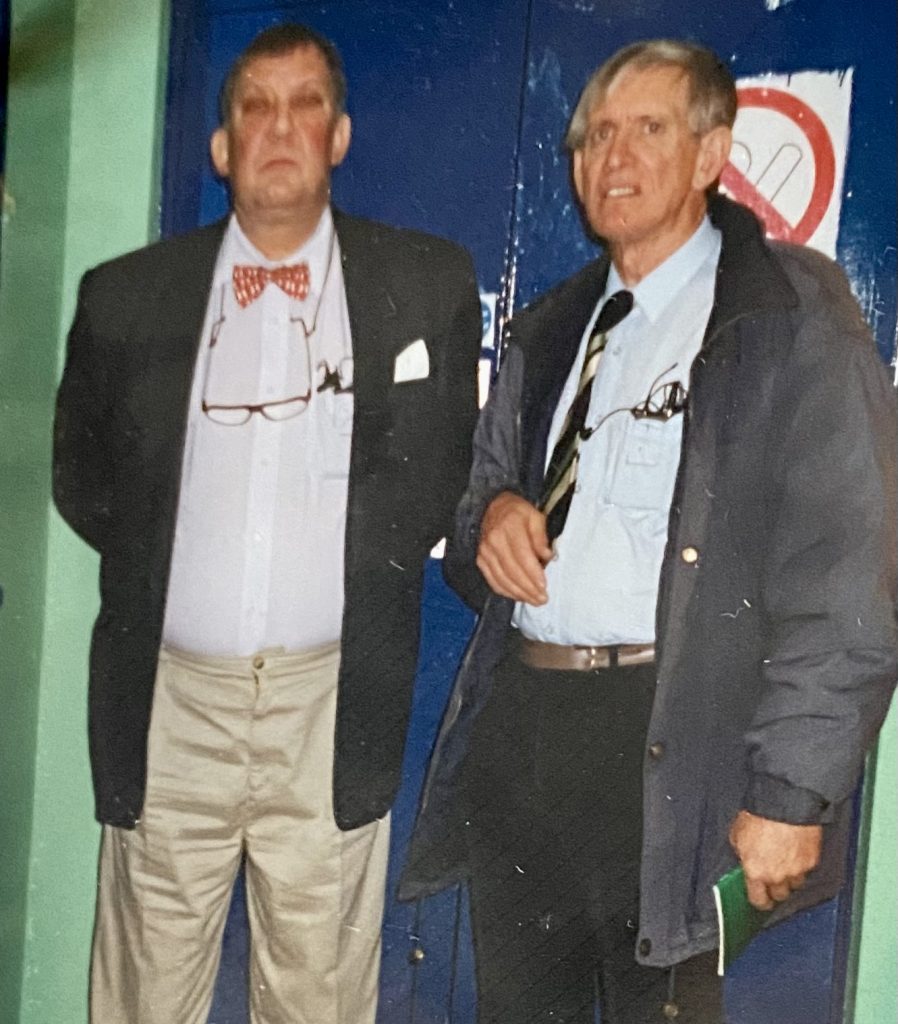

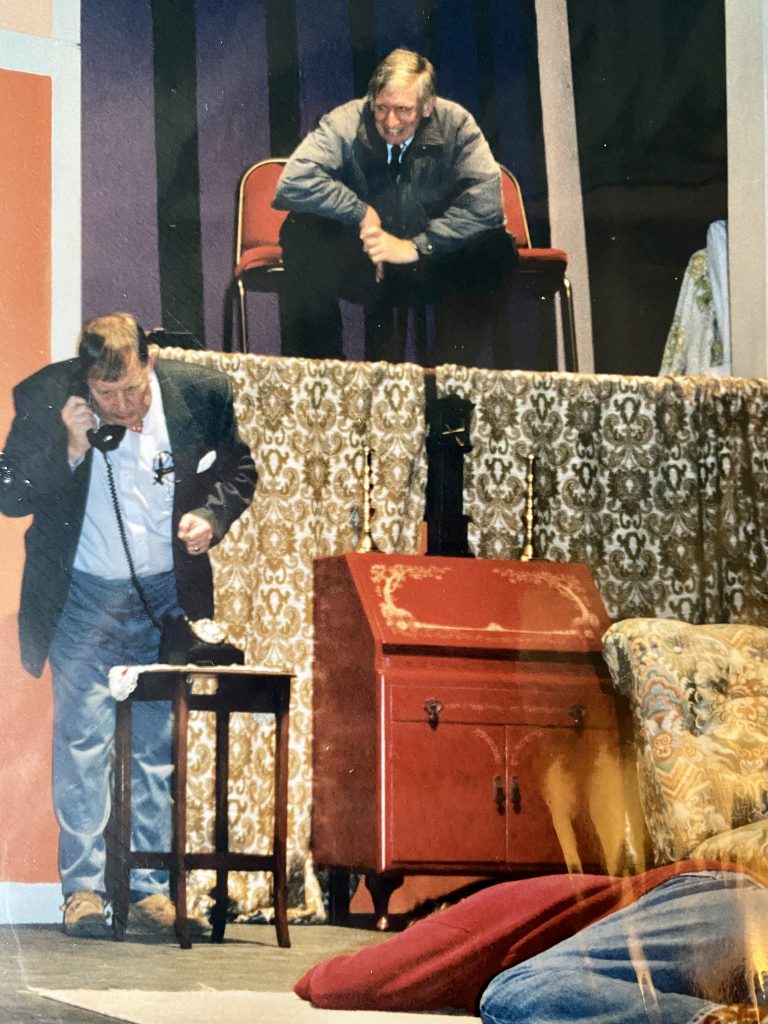

Geoff Guy and John Williams like William were featured in both plays with the former central to both. Colonel Melkett represents the reaction to all things unconventional and lacking in moral fibre, and Geoff dimunicated an intolerance and bullish temperament that was most appropriate. I did feel that this consummate actor could have developed a few more gears to his rage and frustration as he did arrive a little early at what became the zenith of his fury leaving him little opportunities to develop later reactions. There were some nice moments however like his incredulity, sprawled on the floor in front of the rocking chair, and his hailing posture to Brindsley in his bedroom, knees bent and leaning backwards as if his shoes were glued to the floor. Moon did not really offer enough of a contrast on the night and the microphone did not serve the actors well with the timbre rendering some sections inaudible. The exchanges between Moon and Birdboot lay the foundation for the eventual denouement with Puckeridge but I’ll wager few in the audience picked up the connection purely from this performance. Again I felt there was less vocal range in evidence than I felt was required, as Moon moves from mild cynicism to bitterness from whimsy to triumph, but may be the enforced intimacy conveyed through voice amplification conferred this restraint. There was a very nice moment which could have been held longer when he discovered that he was the ‘stranger in their midst’, his auditorium seat taken and his reluctant adoption of the inspector role ‘I’m not mad! I’m almost sure I’m not mad! Good work again then from Geoff, requiring just a little more relish to really impress.

There is a connection between the effect of the acting in the staged play and that in Pirandello’s “Six characters in search of an audience’ for characters in both are presented as in an alternative reality with no oftstage existence. Birdboot then Moon are sucked into this separate reality in much the same manner as cinema has explored more recently in ‘The Truman Show’ or ‘Pleasantville’. There needs to be some slickness to this acting as the stage reality powers inexorably onwards incorporating the two hapless critics. My mention earlier of the snow boots was informed by a feeling that they were too suggestive of a costume/prop dimension that was at odds with this dimension. Your actors gave something of the required two-dimensional focus in their performances. Mrs Drudge is another scene stealing role with her laboured exposition on the telephone and to Simon, her country yokel meteorology and her habit of turning up at just the right moment to hear threats on Simon’s life. Pam Jell affected a heavy limp, dragging one foot behind her such that her progress around the stage was slow and deliberate, and this was effective adding to the humour as she gradually moved into hearing as the threats were delivered although I would have liked more of a reaction on hearing these. There was also a section with Simon where both stood together with similarly clasped hands in front of them, with little or no gesture. The amateur sleuth part at the end was well handled. Philippa Devine’s Felicity was suitably haughty and affected effective poses on occasions, an element that could have been used more often. There was a distinctly awkward passage when Birdboot first entered the action when lines were blurred if not entirely lost but this was largely a fine supporting role. Cynthia had an odd entrance stepping off of the chaise but otherwise Jane Amherst gave a solid performance although she had opportunities to develop a broader characterisation

given the nature of the play style and the number of implied exclamation marks in her preoccupation with Albert. The card game was handled fairly well although the ironies could have been pointed up a little more: “I hear there’s a dangerous madman on the loose’ “Simon?” This address to Simon could be more humorous with quicker, sharper delivery to link him to the preceding statement. The timing in the second card game also faltered a little for some reason. With these slight reservations she was still a fine, support in her scenes.

John Williams appeared in both plays, created the sound effects and designed the publicity material, clearly someone to encourage! His performance as Schuppanzigh was quite effective with measured, reasonable tones,

suitably accented, and stance of misapplied authority. He listened well and his exchanges with the others worked well, although I was not sure the simulated union with the sculpture had a place in these largely celibate (at least on stage) plays and it seemed rather gratuitous in the company of the writers’ wit and invention.

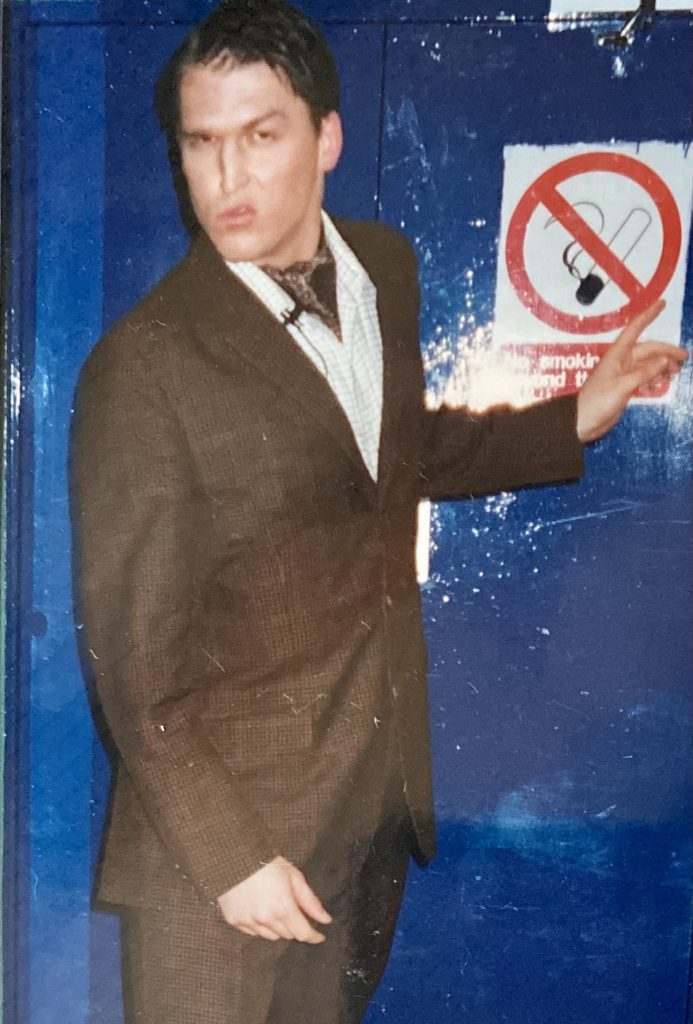

Magnus contrasted well with the electrician – should he have had a feigned Canadian accent that he could dramatically discard when revealed as Puckeridge? His first entry is a lovely moment, to be repeated with Birdboot, but perhaps in this production he had too far to travel when the object actor could have been placed closer either stage right (Simon) or stage left (Birdboot). His delivery of key lines had a fine dramatic authority: I think I’ll go and oil my gun!’ said with knowing glance at audience. The culminating section when all is revealed was very effective. Mike Babb as the seedy Birdboot looked splendid, a sad would-be gigolo, going to seed and lacking any scruples in using his influence, such as it is, to woo theatre hopefuls. His garrulity gave way to bluster, then coy embarrassment on the telephone and finally risible attempts at suavity. There was much to admire in this performance although he must share some responsibility for awkward moments where was the common factor, like the entrance of Felicity and the second card game as mentioned earlier. Nonetheless here was a strong performer in tune with the character and communicating effectively with the audience.

Both plays were steered well under the steady direction of Brenda Read-Brown, and the action of both was clearly mounted on the stage with good use of the width and depth of the space, the stage business in the first worked really well and the progress of both was smoothly delivered. The use of mikes in the auditorium sections was compromised by the hardware, but it was clear what the intention was, and the distancing it conferred upon the characters was most effective when Simon and Hound took the critics’ seats. The body did not really work (confusingly named lan Canoe in the programme?) in that the chaise was not used to cover it and this reduced the opportunities for more humour as Mrs Drudge almost sees it but instead hides it. As it was, the presence of the body, clearly seen throughout the play adversely affected the inner consistency of this separate reality where for example Cynthia entered and did little to avoid seeing what was clearly unavoidably obvious. Mrs Drudge could have been given a sequence of moves in covering it that would have sustained our interest and added to the dramatic irony. One of the features that link these two plays is the requirement for actors to act in repose, where action moves from them to other characters while they remain on stage. As one of many examples, what do the Colonel, Harold and Miss Furnival do while Brindsley and Carol discuss their situation upstairs? There was an uncertainty about these sections that made me feel the actors were a little uncomfortable at these moments. Again the good outweighed the less so and the response from your audience bore some testament to the more important success of having entertained them with these two gemlike plays.

As I finish I am mindful of the further irony of reviewing a play that demonstrates the pomposity of critics, but I do feel that your productions had some élan’ without too much ‘éclat’ (!!!) and, enjoying the evening as I did, I look forward to seeing an extract of this report ‘reproduced in neon’ outside the theatre next time! Finally, if I have in any way offended, remember it is only my opinion and I am totally supportive of your aspirations to bring theatre opportunities to Tewkesbury, actors and audiences. In Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot’, a play reasonably contemporaneous with these plays, the two central characters exchange insults with increasing venom and, after ‘moron’, ‘vermin’, ‘sewer-rat’, and such, the exchange is ended with one declaring the other a ‘critic’ to which the other cannot reply as this vanquishes him totally. Until the next one, all the very best with your society.

Alan Hayes